I’d like to apologise for dangling an LEL blog at you without delivering. It’s been another year of curveballs where priorities have needed to shift and the result is more half written articles that will never be published.

LEL TL;DR

The short version of my 2022 LEL is that I began with zero pressure and thought my odds of finishing were 50/50. I felt strong early on and overcame a mechanical to bridge back to the lead group with an hour’s effort at race pace. I stayed in this group until the first night, when the Howardian Hills broke things up and my knees felt like they’d force an abandon. Thankfully, to my surprise, that was the worst I’d feel all the way around. After a short nap I set off to meet sunrise on day 2 and my body had settled into a rhythm. I maintained a measured routine of sleeping every night and focused on finishing rather than racing. Despite this (perhaps because of this) I still reached London in the top 20 and felt relatively good afterwards. The saddle pain was still too great and remains a priority to resolve. This was a major confidence boost after what had been a terrible year for fitness and a total lack of conditioning, with no long rides for almost three years. [Strava].

2022

I don’t try to hide mental health challenges but, equally, I’ve never actively brought it up. In 1996 I was first diagnosed with depression, at a time when it was far less understood and acknowledged. In the three decades since I’ve learned a lot and found ways to manage it; fitness and cycling being the most effective tool for me. A therapist commented that 2022 had thrown more drama and trauma at our family than most experience in a lifetime. I’d tried to tough it out (by ignoring it) but by autumn it was obvious, even to me, that it was unsustainable and overwhelmed the resources and resilience I had available. I found myself in a depressive hole. I wallowed there for a bit and then very slowly started the climb back out. I’m in a healthier place today but this is a lifelong process of increasing resilience and building routines and tools that help me to better manage mental health.

Lifting

When I started cycling in 2014 I shifted my ideas about physical fitness towards power-to-weight ratios and cancelled my gym membership. I watched as my upper body melted away and I regressed back to a skinny body. We know now that strength training is hugely beneficial to cyclists and especially so for older athletes (and non-athletes too!). My lack of conditioning had forced a scratch in Oman and the physical demands of fatherhood had lit a fire. I’d also seen enough stockier ultradistance and crit racers succeed to realise that being lightweight wasn’t really necessary for me. My knee troubles mean climbing remains the weakest part of my repertoire anyway, so a few extra kilos really won’t make much difference. In August I started lifting again and instantly fell back in love with it.

After a decade away I was basically a beginner again, but with the advantage of mitochondrial memory, which meant I got to enjoy the rapid noobie gains all over again. The first 6-12 months of lifting tend to bring the bulk of your progress, which makes it a rewarding period. After a month of conditioning my soft tissue to prepare for heavier work, I threw myself into lifting and was getting more gym time than saddle time. I don’t think I’ll get back to the 105kg peak of my pre-cycling days but I’ve enjoyed the benefits that lifting has brought back. Some persistent niggles and weaknesses that I expected to live with forever have improved. It’s been hugely beneficial for mental health and has likely offset the reduction in bike training. At the time of writing, I’ve been training heavily for 12 months and have no plans to stop.

Racing

Riding volume is down dramatically. From a peak FTP of 370W in Jan 2022 it had fallen to a low of 315W by August 2022. The long, dreary winter delayed the weekday morning crew getting back into a rhythm in 2023. At the same time, extended challenges in real life meant that I barely trained through February-April. In May I decided to race my way back to fitness. I didn’t have the power but there’s no better way to get it than to go racing. It also freed me up to focus on learning to race better and not just pedal faster. I’ve enjoyed a few good results, with fitness gradually improving. I’ve also enjoyed the process, which is more important.

Aside from a couple of 2/3 races where I had Parlay team mates I’ve largely stuck to Masters racing. I feel the quality of riding at lower categories is declining further and I’m not comfortable with the risks. Too many 3/4 races end in crashes and ambulances. It’s rarely aggression. Typically it’s a lack of awareness of how a rider’s actions ripple back through a field. In the past I’ve tried to point this out in the moment, but we’re not in prime learning mode when your eyes are on stalks and your heart is beating at 190bpm. What’s really needed, in my opinion, is a proper system of training and accreditation before starting at cat 4. How else are new riders ever going to learn the subtleties of racing and safe bunch riding at race speeds?

Masters racing has proved to be hard and aggressive (in a legitimate way) but less reckless. The field have survived years of racing so a typical Masters racer has learnt how to race safely. We tend to have a bit less testosterone and a bit more self-preservation, with the knowledge that we don’t bounce as well as we did in out twenties. It also helps that the spread of power is greater, which tends to string the field out and make for harder racing; most crashes happen in larger bunches. Unfortunately you can never fully eliminate risk.

Man down

Ahead of me a rider moved right and clipped the front wheel of another racer, sending him to the floor. The crash rippled through the pack like skittles, taking down two riders from the next row, and then four. By the time I arrived there were bodies everywhere. My own crash was inevitable and violent. 46kph at the moment of impact. Trying in vain to navigate the carnage, I didn’t have time to take my hands off the bars as I ‘fly swatted’ to the ground. It looks like I’ve landed shoulder-first onto a bike. As the dust settled I reached up to feel the profile of my shoulder, to confirm what I already knew. The physical pain was likely drowned out by adrenaline but, one by one, I began to process all the repercussions of my injury, and these were painful to accept.

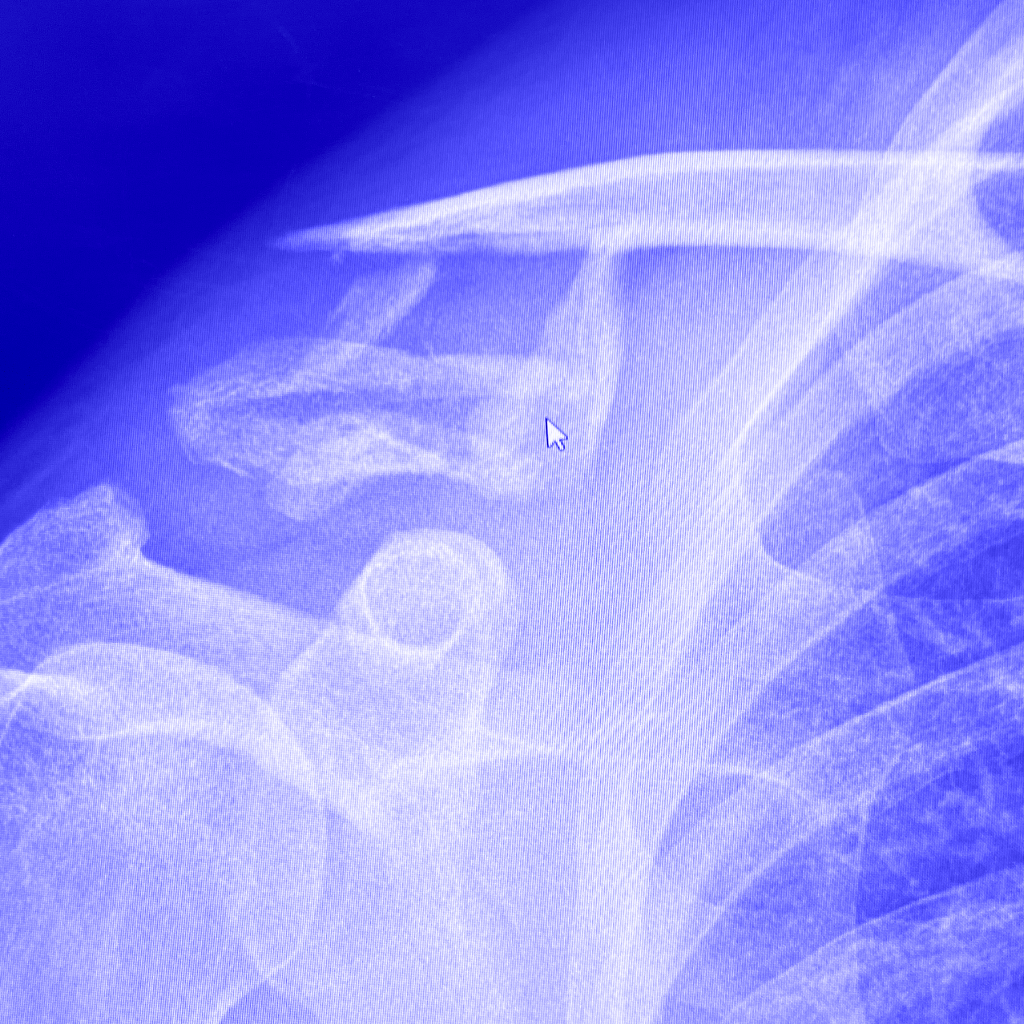

I got a preview of the x-rays at Homerton A&E that night. I’m no doctor but it didn’t look great. A candid nurse confirmed “It’s very screwed”. I’m very fortunate to have medical insurance and was able to work with a specialist surgeon who helps elite athletes (and was prepared to slum it with me for a bit).

A ‘good’ collarbone break is when the bone snaps cleanly, somewhere in the middle. If it’s well-aligned the bone will heal all by itself. If it’s mis-aligned then it typically requires surgery to pin one side to the other. The arm (distal) end of my collarbone had exploded into multiple pieces, so there was nothing there to pin. Rather than a perpendicular snap, the bone had fractured across a long diagonal. This complicates surgery because only healthy, complete bone can be screwed into.

Fortunately the longest available hook plate was just long enough to hack into a solution. Nine days after the crash this was fixed far back on the neck end of my clavicle and hooked underneath my acromion at the other end. The fragments of bone were gathered up and stitched into place. The dagger-like portion of the fracture had cut deeply into my trapezius muscle and come to rest there, so that needed to be repaired. The fragments of bone also included the insertion points of my pec major and deltoid muscles, which were now just floating. The trauma also destroyed nerves and left me without sensation in my right pec, the inside of my right upper arm and the front delt; everywhere you see bruised yellow.

Recovery

The surgery went well. The hook plate inhibits any movement of my arm above 80°, which means the metal work will need to be removed once the bone has completely healed, in around 4-5 months time. I’m looking forward to that as it’s pretty uncomfortable feeling that hook wedged into the joint. I’m writing this six days post-op and the pain has begun to reduce. It was surprisingly intense for the first few days. I must wear a sling 24/7 for the first four weeks to completely eliminate movement. Then I’ll move onto a very basic physio program. ROM will be limited until the plate is removed in winter, and I’ll be restricted in the weight I can lift with the right arm for some time. The nerves will regrow, at roughly 1mm per day, but there may be a permanent loss of sensation around the collarbone itself.

Looking ahead

At the moment I’m strangely energised by the whole process. I’m treating it like I would treat prep for a major race and almost expecting to come out of this stronger. I can’t really rationalise this but I’m assuming it’s my mind’s way of dealing with the situation. I hope it persists because I’ve long feared an injury like this that would rob me of the ability to exercise. For now I’m being disciplined and giving my body total rest (as far as possible with . This initial four week “do nothing” stage is, I suspect, the hardest part. Once I’m able to do some physio work I’m going to throw myself into that. I’m missing the gym so much, so working my way back to that gives me focus. When the doc signs off on it I’ll also start using the turbo for indoor training to try and minimise fitness losses. I’m expecting to make a full recovery but my best guess is it’ll be 8-12 months before I’m back to where I was pre-crash.

I’ve been working towards some event goals for 2024 that I hope will help with focus, motivation and optimism. This may not be the preparation I had in mind originally but, I remind myself: what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

Ouch! All the best with the recovery, man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Been a big fan of your LEL updates. I’m sorry to read about everything you’ve been through. I appreciate you sharing all that you have, it means a lot and gives some of us, in the same boat, a beacon of hope.

I wish you a good recovery and the very best of life to your family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. It’s comforting to know it might be helping others somehow. I hope your own challenges are surmountable.

LikeLike